What actually is Visa?

Visa is a multinational payment technology company that facilitates electronic fund transfers by operating a vast digital network connecting consumers, merchants, financial institutions, businesses, and governments worldwide.

This sounds like a bunch of jargon that makes no immediate sense. I’ll attempt to deconstruct this statement and define what Visa’s product, VisaNet is, and what value it provides to it’s massive user base.

Visa’s real product isn’t a card: it’s a global trust machine. It lets two strangers who use different banks, in different places, speaking different software languages, settle money with nearly zero friction. That machine is VisaNet.

Before Visa: The rise of consumer credit

The merchant’s problem

We’ll start with their credit card payments processing system; as it lays the foundation of how the product was formed and evolved. Let’s start by defining what credit is: Credit is basically getting the value of a good/service now and paying for it later.

Once credit (for small loans) became popular among the common people, it became a pain for merchants to sell on credit because:

- They had to assess the credit worthiness of each individual customer themselves

- It was a headache to manage the scores of these individual customer accounts (their credit report up until that point, what they bought, how much they “spent” etc.)

The consumer’s problem

On the consumer side, It was a pain because they had to travel to either their store or the bank and hand out their entire financial history just so they could buy something on credit.

Most merchants and banks avoided credit for this reason except the Bank of America (BoA; FKA Bank of Italy named so because it mostly provided small loans to underbanked Italians in California). Also, back in that day, banks weren’t allowed to operate across state lines so BoA was confined to California. This gave them a head start providing a lot of consumer loans to the middle class, since they had already worked with them for a long time.

At the same time, payment using cards was becoming popular (i.e. Diners club would let you pay for restaurant bills on credit, Amex travel charge card was also gaining traction).

Bank of America’s Experiment

Bank Americard

BoA combined the rise of consumer credit and payment using cards to provide cards with pre-approved credit for consumers (called Bank Americard), without confining them to just one merchant. This gave customers flexibility over when they could pay their loans.

They convinced merchants to allow these cards because it would provide more value in:

- increased sales volume

- the outsourcing of the the credit process (effectively it BoA’s problem).

The Fresno Drop

As for convincing the customers, they used an unconventional approach: they simply sent 65,000 people in Fresno a credit card and ran ads to demo it.

Delinquency

One issue BoA did not think about well enough was delinquency. They under-predicted how often people would default and ended up losing >$20m (>$250m today) in the process. This was a blessing in disguise since it discouraged other banks from launching their own credit cards.

Because of regulation, BoA couldn’t expand outside of California so they ended up licensing their credit card innovation to out-of-state banks for a cut of cardholder spend. The licencees would then be taught how to run a credit card operation. This plan failed miserably mostly because of pride (banks did want to be turned into BoA outposts), but there were also some deep technical issues that needed to be ironed out.

The Authorization Problem

AKA determining if the customer can afford to make the purchase with credit

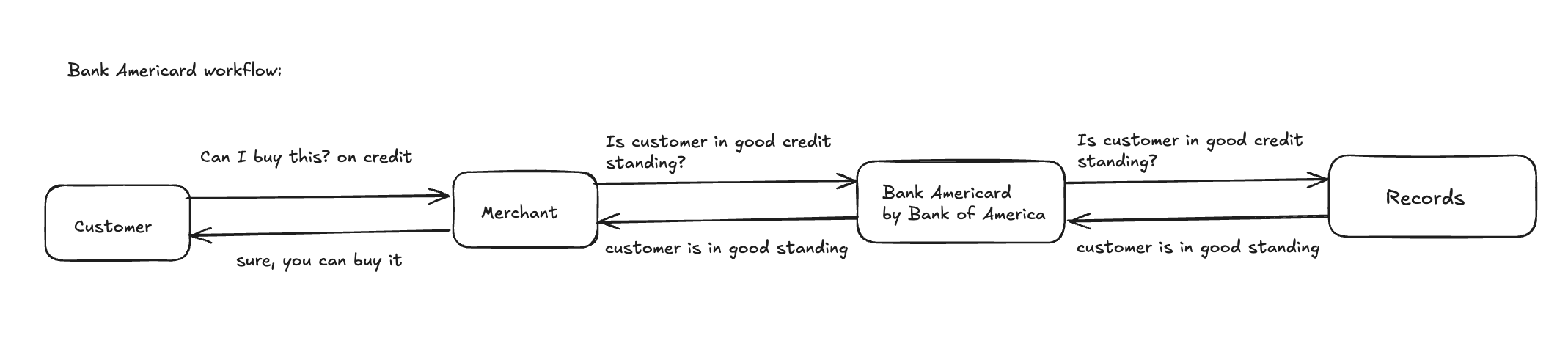

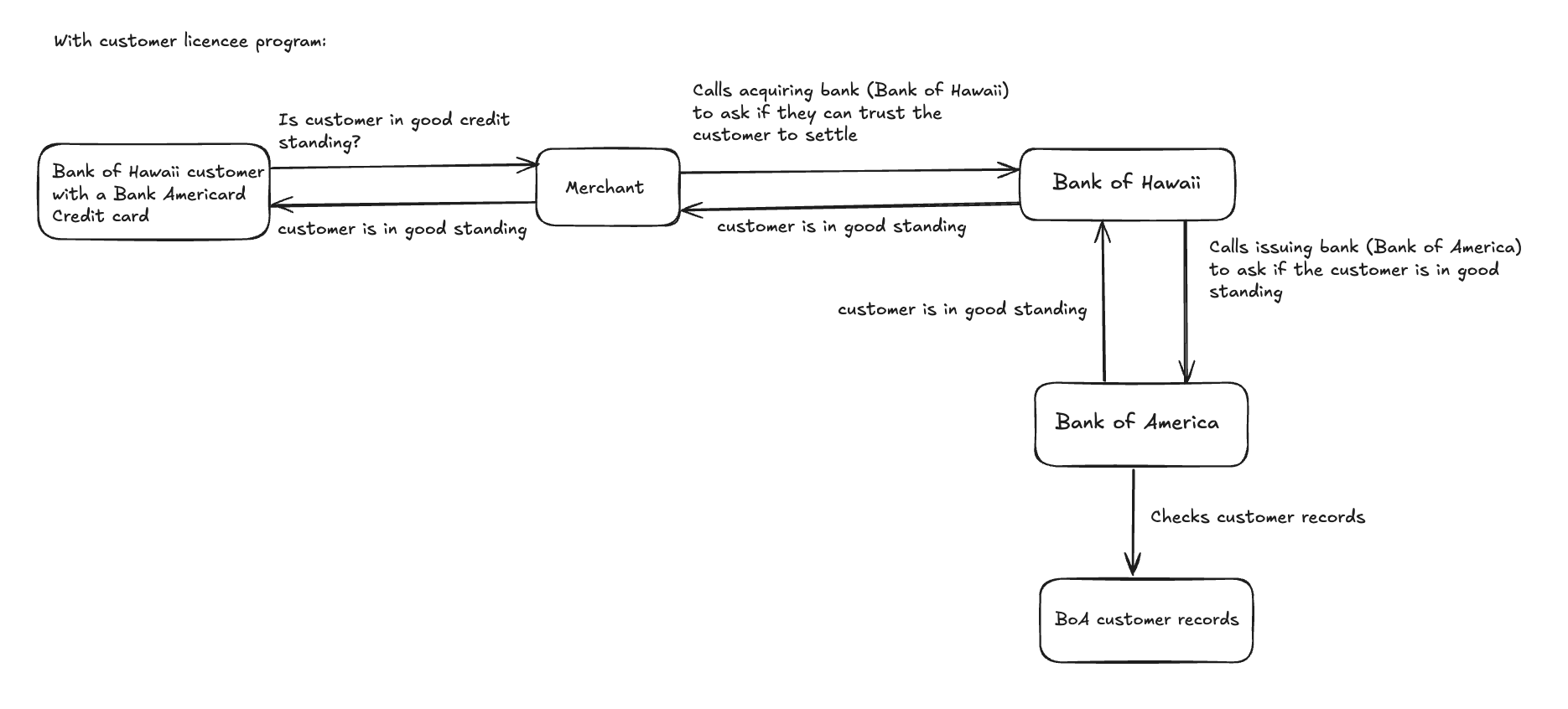

At this point Bank Americard only worked with merchants and customers who would both bank with BoA. What happens when these 2 parties have different banks? To determine if the customer is in good standing to buy on credit, the merchant would have to call the acquiring bank (the licencee), and the acquiring bank would have to call the issuing bank (that gave the customer the credit card; BoA). The official of the issuing bank would have to put the guy from the acquiring bank on hold while they check the customer’s credit worthiness all while the customer and merchant wait around making small talk. And this is all while everything ran smoothly.

The Interchange Problem

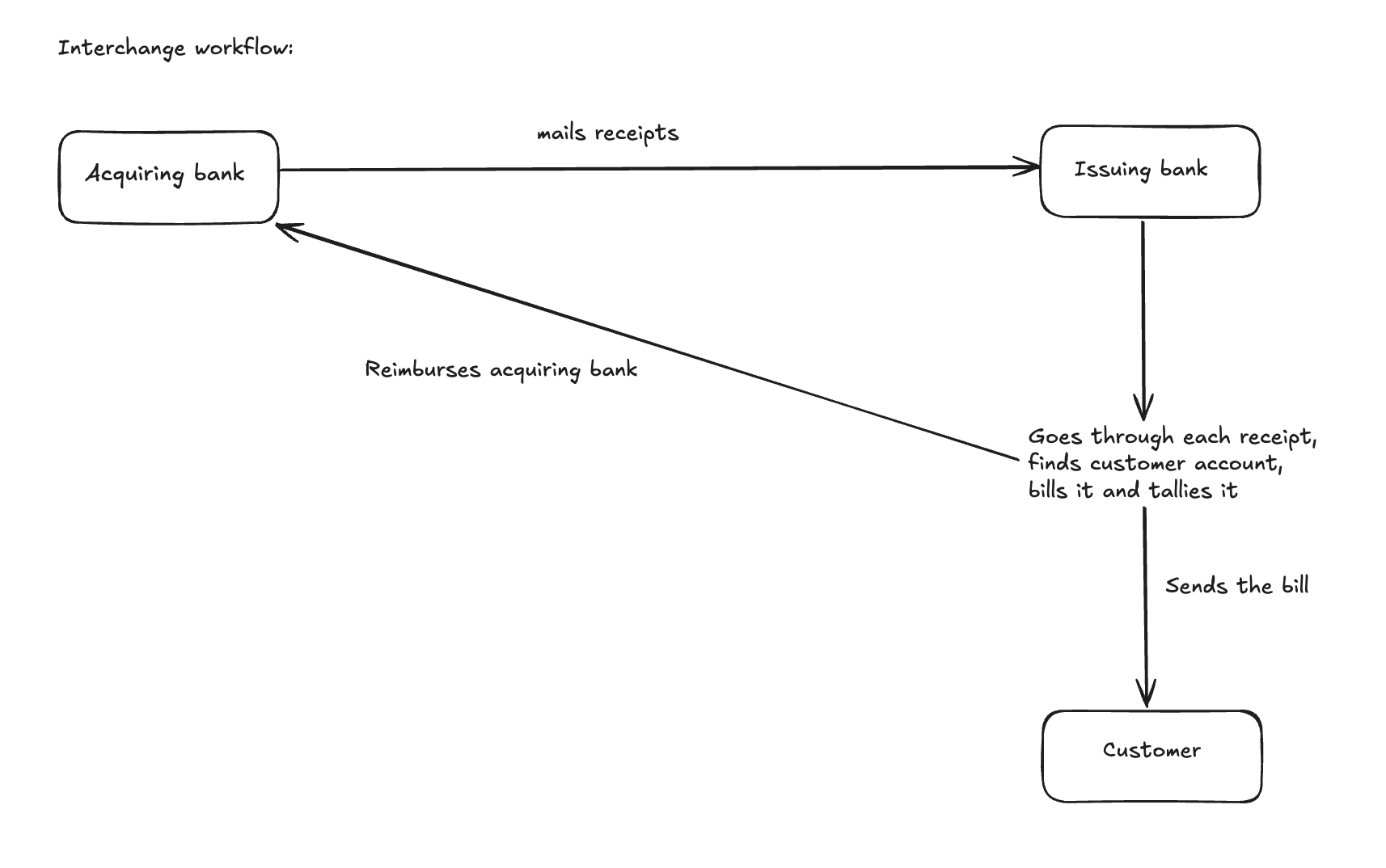

AKA how the acquiring bank and issuing bank settle their accounts with each other. The acquiring bank would mail boxes of paper sales receipts to issuing banks across the country. The issuing banks then had to match up the receipts to their customers’ accounts, reimburse the acquiring bank and then bill their cardholder. This is clearly not scalable since the number of connections would increase exponentially proportional to the number of nodes.

This was a trustless messy system that collapsed under its weight

Licencee banks and acquiring banks had to figure out an easier way to do this, so they formed a committee and one of the members happened to be Dee Hock

Dee Hock’s Visa

The chaordic organization

Dee Hock envisioned a new type of organization; owned by the member banks with ownership measured in business activity rather than stocks and one that was built on trust over competition. Hock’s genius insight wasn’t technical, it was organizational. A card network is fundamentally a coordination problem. Solving it required banks to cooperate on infrastructure while still competing on products. He called this a “chaordic” organization: half-chaos, half-order.

He convinced BoA to give up Bank Americard and spin it off into its own entity, initially called National Bank Americard. It would have the following Operating guidelines:

- Banks would be members

- Everyone gets a say

- Facilitate cooperation

- Voting for change: Any of the guidelines could be changed when given enough votes

This entire program sounded like a cartel in the making and they anticipated some form of government regulation. To deal with this, they convinced the government that the value this system would create would far exceed the benefits of a competitive market.

VisaNet

To solve the authorization problem, they built a nationwide telecom network for banks, a data center to store all customer data + keep the network online at all times and did the necessary training for this new tech.

To solve the interchange problem, they made a massive ledger that sat between the banks. All banks could just log their debits and credits and settle them at regular intervals. This is called an Automated Clearing House.

All while this was happening, other banks had teamed up to form MasterCharge, a direct competitor to National Bank Americard.

They rebranded to VISA, and their marketing campaigns allowed them to frogleap MasterCard (FKA MasterCharge).

VISA is simply a network of banks.

Expansion: Debit cards, POS machines

BTW, all this is for a credit card. We still didn’t have debit cards by this point. Dee envisioned that money would simply be bits.

*“From the beginning, I believed and worked for a transition from the concept of credit card to the concept of a transaction device for the exchange of value, a “debit card”, to use the jargon of the day” ~ Dee Hock, “One From Many”

Law of retail: The harder it is for a customer to buy something, the less they are to do so. The less likely a customer was to do a purchase, the less likely they were to use visa. To avoid this, Visa expanded into:

- making cards machine readable

- digitizing the point of sale terminal

How Visa makes money

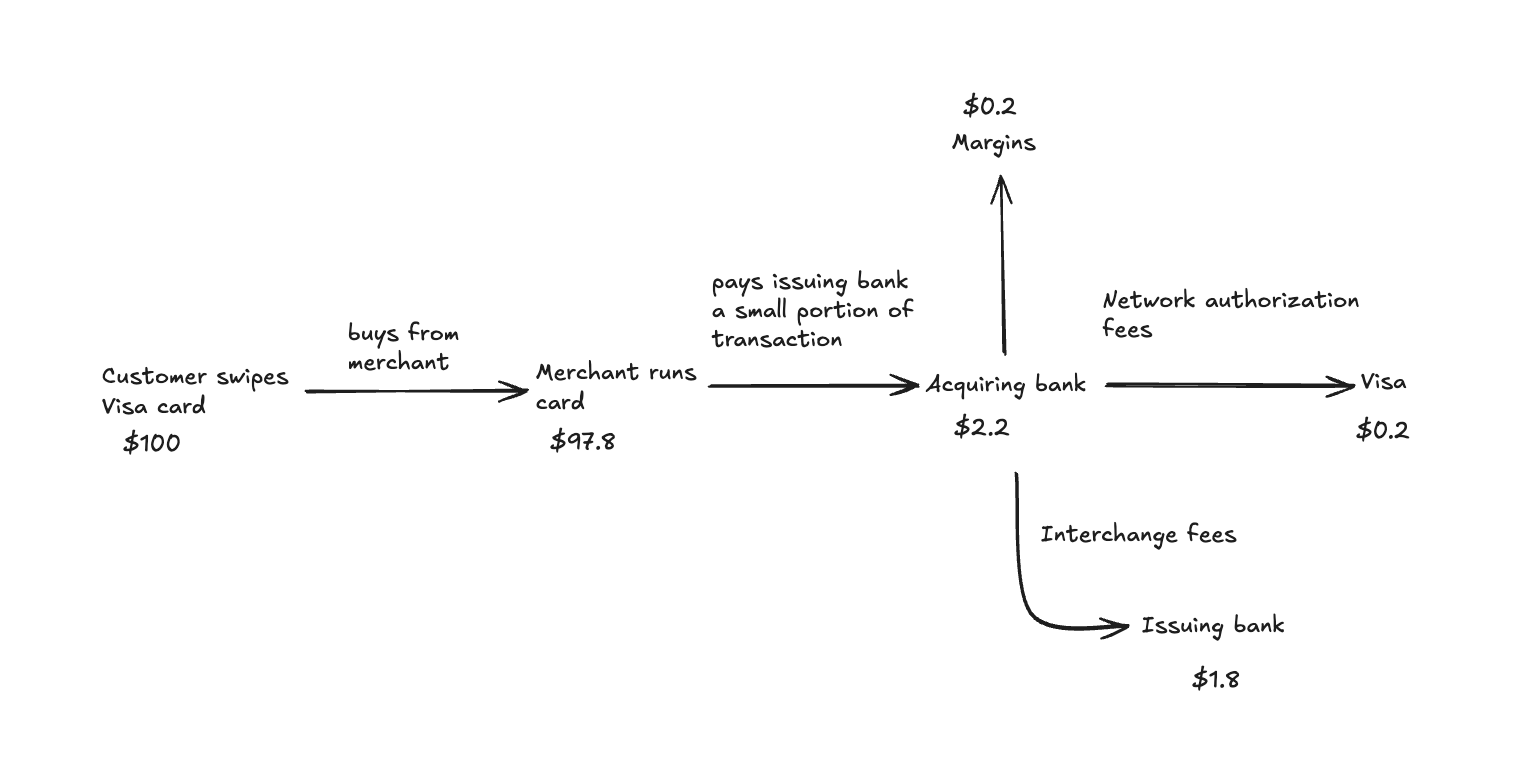

In a typical card transaction on the Visa network, when a cardholder pays $100 at the merchant, the merchant receives about $97.80 after fees, the issuing bank collects about $1.80 as the interchange fee, the acquiring bank (or processor) keeps a small share (e.g. ~$0.20-$0.25), and Visa collects approximately $0.20 (as a network/authorization/processing fee). Visa’s revenue is derived not from the interchange (which goes to issuers) but rather from fees charged to the acquirers and issuers for providing the infrastructure: authorization, clearing, settlement, cross-border and value-added services. Because Visa’s network processes billions of transactions, even a small per-transaction fee aggregates to substantial revenue globally.

As you can see, VISA doesn’t make much per transaction but it adds up ($.2 * 85001 times, every second is a lot of money)

As you can see, VISA doesn’t make much per transaction but it adds up ($.2 * 85001 times, every second is a lot of money)

Conclusion

Visa’s real product isn’t a card or even a payment network, it’s coordination at scale. Every swipe works because Visa creates a layer of trust, built on massive shared infrastructure and the ability to move value with almost zero friction. By standardizing how banks communicate, authorize, and settle transactions, Visa turned a messy system of bilateral relationships into a single global protocol. What they actually sell is the ability for anyone, anywhere, to transact with anyone else instantly, reliably, and almost invisibly. In many ways, it is the dream startup that was never a startup. Clear value basking in the glory of global network effects.

References

People Still Don’t understand Visa by John Coogan

Visa Wikipedia page

Visa’s Debit card monopoly by Asianometry

Acquired Podcast: Visa